In the mid-1970s, four beat cops patrolled Main Street in the evenings. They walked in pairs, one on the west side of the street, the other on the east, up and down between Portage Avenue and the underpass just past Higgins. When they came to the end of this beat, they turned around it and did all over again.

Main Street was at something of a crossroads then. Social services and missions were found there, but so were branch banks, sporting good stores, and restaurants. The skid row element, which owed itself mainly to the seedy hotel bars, was still just one part of a much more complex, heterogeneous street.

Still, it could be a rough and violent place, particularly on weekend nights, but the cops kept order as best they could. As brutal (and unabashedly racist) as some of them would have been, their walking on foot at least made them a part of the public life of the street — and not just when they were responding to an incident. On foot, an officer was able to see both the good and the bad more clearly.

[related_content slugs=”winnipegs-most-perpetuated-myth-downtown-is-dangerous,winnipegs-most-perpetuated-myth-a-response” position=”right”]

Beat patrols put the police in contact with people: the most hardened criminal holding court in the back of a hotel bar; the most desperate homeless man slouched in a doorway; and the countless decent, ordinary people going about their business. Regular contact built a more civil, trusting relationship between police and citizen, and also allowed the police to create local networks of intelligence-gathering.

Like virtually all police forces in North America, however, Winnipeg’s fully abandoned the beat patrol in favour of the squad car — a much more invasive and sensory-deprived method of patrol.

This change in tactics was just one symptom of a broader approach to urban planning and city life after World War II. It was the age of atomized individuals, freed from their social nature by technology, and by increasingly centralized governments and institutions. Not only were urban contact, diversity, and concentration no longer necessary downtown, they were undesirable.

City building, planning, and governance came to function under the principles of homogeneity and control; separating different people and the different things they do. The proliferation of the automobile meant people no longer needed to walk anywhere. New buildings downtown were not only large but internally-focused, separated by arbitrary “green space” and the fast-moving traffic of efficiently-functioning roadways.

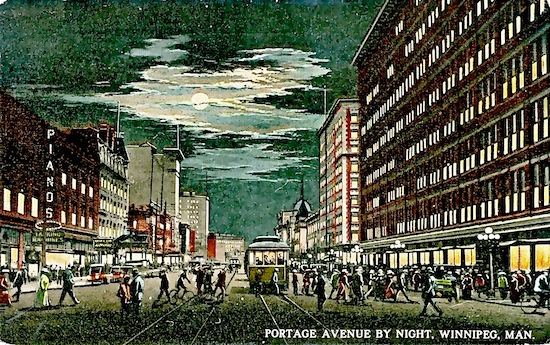

Though all of this was done with good intentions, the built environment that emerged helped create downtown’s current safety issues (both the reality and the perceptions). People are afraid to walk from Portage Avenue and Broadway in the evenings. Not simply because there are a few dingy hotel bars that attract a rough-looking crowd, but because there is seemingly nothing else but that.

***

Six of the ten of the seedy hotel bars that existed on the Main Street strip in the mid-’70s are now gone, but the old skid row problems are still there, and more visible than ever. Decades of publicly-led urban renewal acting as socioeconomic revanchism has not pushed the problems of deeply entrenched poverty away; it has spread them around, across all of Winnipeg’s sprawling downtown.

Today, Centre Venture, a public development corporation, carries on under this same belief that downtown can successfully be as socially and spatially compartmentalized as the suburbs. With heavy financial backing from the City, Centre Venture is desperately buying up run-down hotels near the MTS Centre. To put it plainly, this is in attempts to keep the drunk indians cooped up around Main and Higgins, safely away from drunk white bros in for a hockey game. (The irony is that it was Centre Venture that led the bulldozing rampage that further decentralized Main Street’s skid row in 2008.)

In contrast to this kind of thinking, it seems that many residents of the Exchange District, one of the city’s wealthiest neighbourhoods, do not mind sharing the sidewalk with people of all kinds of backgrounds. They also don’t seem to mind having various types of housing in their neighbourhood, including single-room occupancy hotels and other affordable housing options. (This becomes clearer when one remembers the informed choice these condo- and apartment-dwellers made in moving to the neighbourhood in the first place.)

They don’t want homogeneity, they simply want livability, and the ability to get to sleep at night. (In the Exchange, the neighbourhood’s ostensibly “upscale” nightclubs — which seem to escape the recent moral crusading of the Centre Venture Temperance League — frequently come up as a greater detriment to this than a handful of drunks hanging out by the Woodbine.)

***

There are, however, legitimate safety concerns downtown. As one anonymous comment left on my blog cautioned several years ago, the debate around safety downtown must always “respect the fact that real people are being excluded from real public spaces by real threats and real abuse.” These aren’t always paranoid, racist suburbanites; these are sensible people that live, work, and go to school downtown. Their concerns need to be listened to.

Downtown Winnipeg is unsafe in some places and at some times. This is and always will be a rough town. But it’s one where it’s still possible to learn to live together and share the same spaces again. A meaningful, diligent and comprehensive safety strategy is needed, and this must be part of a greater move toward a more humane, mixed-use, and diverse downtown.

The greatness of cities is the ability for strangers from different backgrounds to live and go about their business in peace and civility. It’s in the centre of the city where this should most strongly and clearly manifest itself.

___

Robert Galston likes to write about Winnipeg, urbanism, and other very, very exciting topics. Follow him on Twitter @riseandsprawl

For more, follow us on Twitter: @SpectatorTrib