Prairie towns, from Downtown Calgary to Herbert, SK, generally follow a street pattern of rectangular blocks of uniform dimensions divided by a perpendicular grid of streets. This grid system, which first came into popular use in North America in the 19th century, were embodiments of the ideals of its age: rational, democratic, and utilitarian. It was easier for developers to subdivide and build upon, and straightforward for pedestrians to get around in.

As new towns sprang up, the location of the post office, train station, large hotel, or bank determined where commercial developments would cluster, and what would form the centre of town. This is why the street leading away from the railway station (or one that intersects with that street) would usually become the main thoroughfare.

As Prairie towns grew and prospered at the turn of the century, some consideration was given to laying out streets according to more romantic notions of town planning, such as the Crescents in Regina’s wealthy West End. By and large, however, the grid system marched onward until the second half the twentieth century. (By then, in the age of the automobile, pedestrian connection was no longer a planning consideration, and the grid system was replaced by the more profitable system of curvilinear streets and cul-de-sacs.)

Though Winnipeg is not much older than most towns in the Prairies, its street system is anything but regular. Much of it exists as a physical expression of the city’s history as a fur trade centre, farming settlement, and fledgling boomtown.

Busy streets that radiate out from the city centre — Portage Avenue, Main Street, Pembina Highway, St. Mary’s Road — were first used as trails for fur traders. Wellington Crescent, which one might think winds its way through Crescentwood to create some sylvan charm in Winnipeg’s original suburb, actually follows a trail used by Aboriginal people long before European settlement.

Many streets came as a legacy of the Red River Colony survey of 1813, which laid out long, narrow farm lots that were roughly perpendicular to either the Red or Assiniboine Rivers. Today, two centuries later, new developments as far out as Headingley and St. Andrew’s are planned within the framework of these ancient property lines.

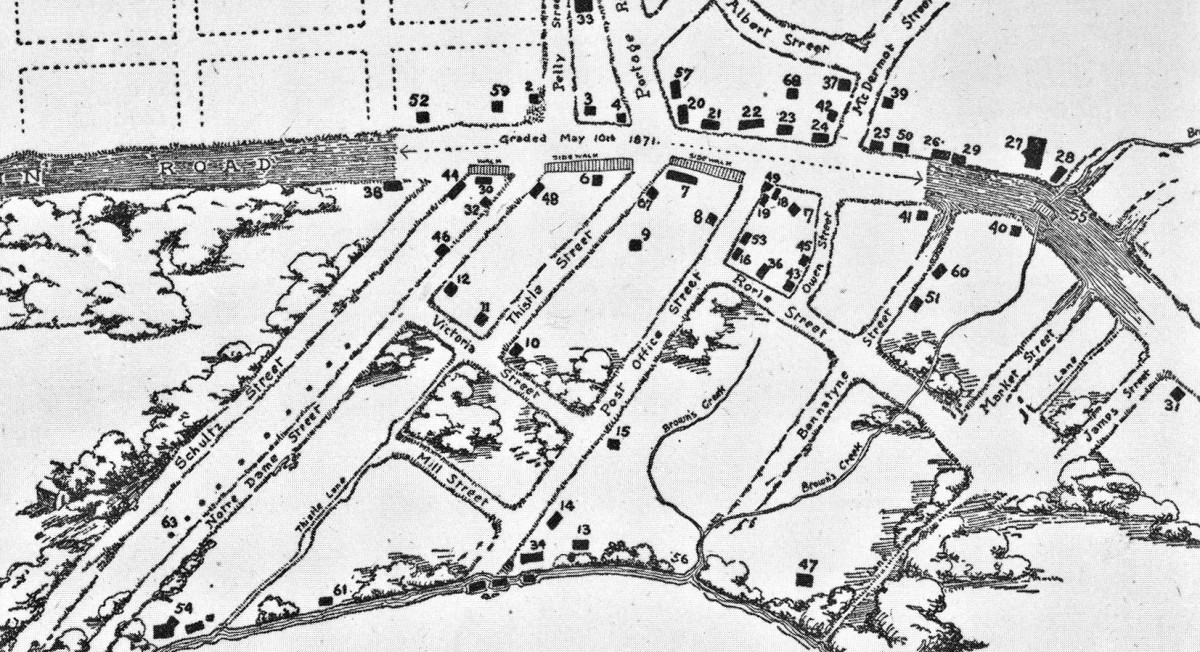

When urban development began in the 1860s, it clustered along Main Street at the intersection of Portage Avenue. The old river farm lots on either side of Main (in today’s Exchange District) formed the basis of an ad-hoc, uncoordinated networks of lesser streets laid out by whoever owned that particular piece of land.

One early attempt at planning regularity was in 1874, when the Hudson’s Bay Company surveyed a regular grid of rectangular blocks on their land reserve south of Notre Dame Avenue and west of Colony Street. (This included a tree-lined boulevard called Broadway.) Portage Avenue, which made its way across the reserve at an angle, was not a part of the Company’s plan. In the end, traditional travel patterns and growing commercial interests on Portage Avenue prevailed, and the old fur trade trail that led to Portage la Prairie remained, and would become the city’s premier thoroughfare.

This early network of streets was augmented after the building boom of the early 1880s. With City Council not in the business of doing much to cause great public expense, or hamper the real estate market in the short-term, the ad-hoc street system of the 19th century remains largely intact today.

The odd angles this street system created would shape many of the buildings downtown. The curved facade of the Confederation Life Building follows a bend in Main Street at a spot where a creek once ran. Others, like the trapezoidal Lindsay Building and the triangular Winnipeg Art Gallery mark places where the Hudson’s Bay Company’s street plan merges with the old Selkirk river lot system.

Motorists, particularly ones new to the city, may decry Winnipeg’s confusing jumble of seemingly random “donkey paths” (as one local newspaper columnist likes to call our streets). When built up with buildings, the street system relieves the monotony of a featureless geography, and create texture, variety, and a sense of enclosure that the regular, perpendicular grid can’t do. The Exchange District, one of the city’s most cherished neighbourhoods, owes much of its visual charm to the vistas created by its irregular grid of crooked streets.

Taken together, Winnipeg’s street system is unique not only among the Prairies, but across North America. Like many of this city’s oddities, it’s something that should be celebrated.

__

Robert Galston likes to write about Winnipeg, urbanism, and other very, very exciting topics. Follow him on Twitter @riseandsprawl

For more, follow us on Twitter: @SpectatorTrib