PART TWO: 1912-2012

[related_content slugs=”two-centuries-on-point-douglas-part-one-1812-1911″ description=”Part One” position=”right”]

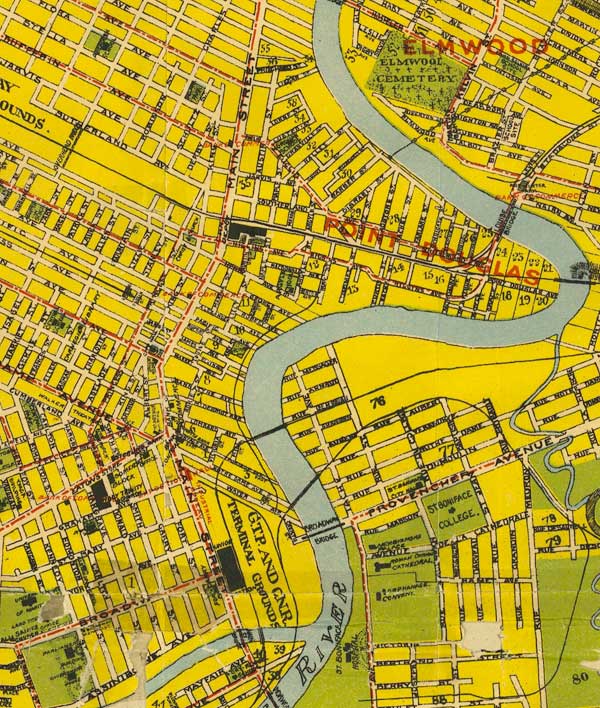

This year marks the 200th anniversary of the arrival the Scottish settlers who first established an agricultural colony on Point Douglas in 1812. Located along the Red River a couple of kilometres north of the Forks, Point Douglas would play an essential role not only in the history of the city of Winnipeg, but in the development of Western Canada.

Today, Point Douglas is one of Winnipeg’s most enigmatic neighbourhoods. To explain where it is to lifelong Winnipeggers can take some effort, to say nothing of having them navigate its jumbled, irregular grid of small streets for the first time. But even if many don’twhere it is, there’s a dual perception, in Winnipeg’s collective consciousness, of what Point Douglas is: both a cesspool of crime and dysfunctional poverty, and a neighbourhood experiencing re-investment and a significant influx of new immigrants and hipster artist types. Neither perception is entirely wrong, and often, this duality is found on the same street. Within 200 feet of where Lord Selkirk’s settlers arrived, there are both new condo developments and the campsites of the homeless among the banks of the Red River.

This is a brief and selective timeline of the people, places, and events that helped shape the Point Douglas neighbourhood of today. In Part Two, we look at the crowded immigrant neighbourhood that had emerged during Winnipeg’s boom years, and how it responded to crisis and decline through the 20th and early 21st century.

1913 – A global recession freezes up the British investment capital that had poured into Winnipeg and supported the dramatic building boom that had characterized the previous decade. Four years of world war, which would break out in 1914, followed by another several years of recession and economic uncertainty, effectively ended Winnipeg’s dramatic boom period.

When prosperity did return in the mid-1920s, Winnipeg found that the game had changed. The Panama Canal that opened in 1914, and changing Federal transportation policies in the early 1920s, would diminish Winnipeg’s position as the uncontested centre of Western Canada’s economy. Added to this, the old business elite that had led the city’s rise at the turn of the century was now old, out of ideas, and ill-prepared for these changes. Rather than adapting to this new, competitive reality, Winnipeg developed a political culture of defeatism: since Winnipeg’s growth had come at a time of favorable Federal regulations and policies, prosperity was seen as something given or taken away by government and outside circumstances, rather than as something that can be created.

All People’s Mission on Euclid Avenue, circa 1912

1919 – Steel workers at the Vulcan Iron Works on Maple Street North join employees at the city’s other large metal companies in a strike. Soon after, the rest of the city’s unionized workforce walk off the job in sympathy with the metal workers. Underlining the general strike were the continued deterioration of real wages, as the cost of living remained high following the war. The strike culminates in June, in a clash between demonstrators and mounted police on Main Street that leaves one person dead.

Leading up to, and during the strike, Victoria Park, a small park at what’s now Waterfront Drive and Pacific Avenue, holds outdoor meetings when crowds became too large for the Labor Temple on nearby Rupert Avenue. In the early 1920s, Victoria Park would be sold to the local power utility who would build a steam plant there. (The plant was demolished in the early 2000s, and is now the site of new condo developments.) The proceeds from the sale of Victoria Park went to buying and developing Norquay Park on the banks of the Red River in north Point Douglas, around the corner from the former home of Manitoba Premier John Norquay.

Some would later see the sale of Victoria Park–an important site for the strike movement–as the City of Winnipeg’s “revenge” for the chaos of 1919. Whatever the case, the sale was approved by the city’s first Socialist mayor, S. J. Farmer.

With such high population densities, and an absence of any meaningful land use zoning, a high number of corner stores exist throughout Point Douglas in 1919. This is particularly true on Euclid Avenue, where more than 20 establishments — grocery stores, pharmacies, barber shops, and a restaurant — are in operation. Close to either side of the CPR tracks, a small enclave of black Canadians and Americans begin to emerge on side streets off Higgins and Sutherland Avenues. Mostly employed with the railway, several businesses and churches also operate. Today, Pilgrim Baptist Church on Maple Street is a remnant of Winnipeg’s largely unknown black neighbourhood.

Children play in the wading pool at the newly-opened Norquay Park at the foot of Lusted Avenue, circa 1926

1930s – While Winnipeg’s economy was slow but steady through the late 1920s, the Depression of the 1930s hits the city hard. Many of the new immigrants that arriving in Winnipeg and settling in Point Douglas find themselves unable to gain even the most menial jobs. There emerges an extended network formal and informal trade, co-operation, charity, and public relief programs. Cash poor household barter with neighbours and corner store proprietors. Lumber companies such as Brown and Rutherford on Sutherland Avenue invite people to take what scrap lumber they need. City-owned land along Higgins Avenue is used as public vegetable gardens.

On the southern banks of Point Douglas, where Lord Selkirk’s settlers built Fort Douglas more than a century before, hundreds of unemployed men camp out in what became known as Winnipeg’s hobo jungle. While homeless people had been living along the banks of the Red for as long as the city had existed, the number swells dramatically during the depression, as transient men from across the country camp out, roughly from the foot of Pacific Avenue, to the foot of Curtis Street. Among the hobo jungle, a charismatic gangster and amatuer boxer from Point Douglas named Mickey Shane operates gambling rackets and sells home brew.

By the 1930s, much of the Jewish merchant class that had settled on the quiet streets in Point Douglas in the early years of the century have moved out, moving toward the promised lands on Scotia Street and in River Heights. Some Jewish families remain, however, including that of Let’s Make a Deal! host Monty Hall, who was born and raised at 107 Hallet Street.

Looking down Main Street from Higgins Avenue, circa 1932

1941 – Canada’s involvement in the Second World War gets factories in Point Douglas humming again, and Vulcan Iron Works proudly produces a million shells for the Allied cause. Many of the new immigrants and the men of the hobo jungle either enlist or find work. However, the shortage of building materials and skilled labour means that investment in housing has largely frozen, and the physical condition of housing in Point Douglas continues to decline, causing groups like the Social Planning Council to consider the neighbourhood a slum. Exceptions exist, and one man would single-handedly demolish the old John Norquay house on Hallet Street, building two small houses in its place with the old materials.

Meanwhile, William Stephenson, a 44 year-old British intelligence officer who grew up on Syndicate Street on the east end of Point Douglas, advises President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill on matters of wartime intelligence, and establishes “Camp X” in Whitby, Ontario as a training ground for Allied spies. After the war, Stephenson would be knighted for his efforts, and his work would help lead to the creation of the Central Intelligence Agency. He would also reputedly serve as inspiration for spy novelist Ian Fleming’s James Bond character.

Kids on Granville Street, circa 1948

1950 – The worst Red River flood peaks in in Winnipeg in early May. Most of Point Douglas is evacuated, and the neighbourhood comes under the control of the Army and Red Cross volunteers, who base their local operations out of a house on Euclid Avenue. The waters swell over the banks of the Red and turn many streets into canals.

In the long term, however, the flood had the inadvertent effect of improving the neighbourhood’s physical condition, as federal disaster relief assistance programs not only repair flood damage to houses, but, after years of depression and war, upgrades them to more modern standards.

Aerial photograph showing the extent of the flood waters in 1950

1959 – The Disraeli Bridge is built through Point Douglas, displacing dozens of houses and businesses on both the north and south sides of CPR tracks. This is only the first phase of what Winnipeg officials hope will be an extensive freeway network, which would see most of south Point Douglas (as well as The Forks and neighbourhoods like West Broadway) cut up by new above-grade roads and on-ramps. Of course, practically none of these later phases would ever be built.

In spite of some improvements to Point Douglas’ housing stock, and the arrival of a new wave of European immigrants after 1945, planners, social reformers, and political figures see the old, mixed-use neighbourhood as a slum, and call for an urban renewal program. Point Douglas residents object to this slum designation, rightly fearing the rapid decline would arise from it, and from developments like the Disraeli Bridge. In 1959, residents form an association with the dual purpose of fighting against big political ideas for the area, as well as addressing particular problems that are occurring in the neighbourhood.

In 1959, Lily Sparrow dies in her family home on Euclid Avenue, which her father, Edmund Barber, had built with logs nearly a century before. Born in the house in 1872, and a granddaughter of Robert Logan, Sparrow was one of the last living links to Point Douglas’ pre-urban past. In the 1970s, the Barber house would be acquired by the City of Winnipeg and sit vacant for decades–the subject of many activist’s attempts to to redevelop it, and even more arsonist’s attempts to burn it down. It would finally be restored in 2011, and today is used as a seniors drop-in centre.

The Barber House sits tucked away on Euclid Avenue in 1959

1969 – The shortcomings of large-scale urban renewal and massive public housing developments are beginning to be seen in cities across North America. The Canadian government announces a renewal program for north Point Douglas that would improve existing properties, and work within the fabric of the neighbourhood: home renovation programs and smaller-scale infill developments instead of wholesale bulldozing. But while north Point Douglas is seen as a strong and unique neighbourhood worth saving, the population continues to shrink, and the number of corner stores declines by more than half, from 13 in 1965, to 6 in 1972.

Some of the new immigrants arriving in Winnipeg from Europe and Asia would settle in Point Douglas in the 1960s and ‘70s, but the most dominant new group would be Aboriginals arriving in the city from reserves. In 1978, the Manitoba Indegenous Cultural Education Centre moved into the old Methodist mission on Euclid and Sutherland Avenue. The grand Canadian Pacific Railway station on Higgins Avenue would become the Winnipeg Aboriginal Centre after the CPR ended passenger service in the late 1970s.

City Planning map from 1966

1988 – The Free Press reports that groups of kids are running around the streets of north Point Douglas damaging property and terrorizing residents, and overall the late 1980s and ‘90s are considered the lowest point of urban decline in Point Douglas. As immigration patterns are more decentralized, and as the city’s population stagnates, many houses in Point Douglas are bought up by slum landlords who seek to extract the most revenue with the least investment possible. A number of rooming houses in the area become centres of drug trade and violence, and many aging residents are afraid to walk down the streets they had watched their children grow up on. In the 1990s, property values across Winnipeg would plummet dramatically, particularly in inner city neighbourhoods like Point Douglas where arson becomes an ongoing concern.

In spite of this, various incarnations of the Point Douglas residents’ committee battle against indifferent City departments, slum landlords, and illicit street activity. A small number of weirdo bohemians, recognizing the area’s unique feel and slower pace, begin to buy houses (usually paying no more than $25,000). Visionary or simply eccentric, these new arrivals begin the optimistic projections that Point Douglas will become Winnipeg’s next cool cheap neighbourhood.

House on Hallet Street, circa 1996

2012 – It seems as though the claims of Point Douglas being the city’s next “it” neighbourhood can actually be substantiated somewhat. Increased immigration to Winnipeg, rises in real estate values, and lowered rental vacancy rates throughout the late 2000s all put new pressure on Point Douglas as a residential area. With safety and quality of life issues being effectively dealt with by active residents, and with things improving in the nearby Exchange District and along Waterfront Drive, Point Douglas has become an increasingly desirable option for buyers and renters wanting proximity to downtown and a little bit of hipster/street credibility.

Old problems remain, often alongside the signs of progress. A few residential streets continue to have high levels of social dysfunction and crime. Vacant industrial sites are likely to remain held by speculative owners waiting for a big government payout (a perverse unintended consequence of government involvement in urban renewal is that it freezes private investment in urban renewal).

As Point Douglas continues to evolve, it is a place where many remnants of its past live on. Customers can still be heard haggling in Polish over the price of kulbassa at Metro Meats, Euclid Avenue’s remaining corner store. The (predominantly Portuguese) congregation of Immaculate Conception Roman Catholic Church on Austin Street still parade through the neighbourhood on certain feast days. Brown and Rutherford Lumber Company, which first went into business in 1872, continues to operate on Sutherland Avenue. In 2012, a new metal works company moved into the old Vulcan Iron Works building.

The trains can still be heard coming down the Canadian Pacific mainline, as they have for 130 years. Great trees and staid houses from the 19th century stand alongside the strange grid of streets laid out according to the property lines of Lord Selkirk’s colony. And the Red River, severe as it is serene, winds around Point Douglas as it has since time immemorial.

Condo development planned for Macdonald Avenue near Waterfront Drive. Design by 5468796 Architecture.

—

Robert Galston likes to write about Winnipeg, urbanism, and other very, very exciting topics. Follow him on Twitter @riseandsprawl