Pre-construction for Edmonton’s new Walterdale Bridge began earlier this month. Marketed by the city as a more elegant design than the steel truss bridge built 100 years ago, the new signature bridge will be defined by its single graceful arch. While demolition of the old bridge might represent a break from Edmonton’s industrial past in exchange for a more refined future, dispensing with the past is not a simple matter. The Fort Edmonton Cemetery and Burial Grounds is located on the northern bank of the North Saskatchewan River in the community of Rossdale, just next to the Walterdale Bridge exiting intersection. Due to the recent rediscovery of this site, development in the Rossdale area has become a contentious topic in Edmonton. After lengthy preparation for this infrastructure project, it’s becoming clear that the Walterdale Bridge is bound up in a dynamic and historical relationship between urban neighbourhoods, local Aboriginal bands, corporate enterprises, and municipal, provincial and federal administrations.

[related_content slugs=”corporate-influence-and-aboriginal-consent-in-alberta-bill-c-45,full-time-kindergarten-in-alberta-is-a-womens-issue” description=”More from Cynthia Spring” position=”right”]

Unlike other proposals to revitalize Edmonton’s local infrastructure and economy (such as the new downtown arena for the Edmonton Oilers), the city’s spending budget is not the only factor influencing approval for the construction of the new bridge; the historical significance of its construction site has delayed the project for some time now. Documentation of found human remains reveals that contractors working in the Rossdale area throughout the 20th century were aware of the burial ground. It was not until 2001, however, that the site was brought to the public’s attention and regained a certain authority over infrastructural development in Edmonton. Since this rediscovery, the Rossdale memorial has been built and the city has protected the site from further development. In order to construct a new bridge, the city must be mindful of the risks that will accompany the disruption of the ground in this area, as well as the historical significance of the demolition of the Walterdale Bridge.

The century old Walterdale Bridge is a remnant of a fundamental transition that occurred in late-19th century Fort Edmonton. Just thirty years prior to the construction of the bridge, the Hudson Bay Company relinquished its authority over Edmonton’s economic trade and distribution of property. Beginning in 1880, land previously owned by HBC was subdivided and sold to newcomers to the city. This redistribution of land helped to transform Edmonton’s financial system into a free market economy rich with resources and commercial opportunities. Due to these systemic changes, communities housing people of both Aboriginal and European descent began to appear outside of Fort Edmonton’s walls; the neighbourhood now known as Rossdale was one of these communities.

The area now known as Rossdale was originally Papaschase land. In the 1880s, the land was sold to their namesake, Donald Ross, by HBC. Ross helped to develop the Ross Flats into one of the first residential zones in the burgeoning city of Edmonton. Meanwhile, as infrastructure developed within these new communities, the Papaschase Band struggled to establish a reserve on the opposite side of the North Saskatchewan, within the present boundaries of the city. After signing Treaty 6 in 1887, the Papaschase Band agreed to sell the land already claimed by HBC in exchange for, among other things, a protected band reserve in Edmonton. However, in 1911 Canada’s Federal government made an amendment to the Indian Act which allowed for the expropriation of Indian lands for the sake of public works. This meant that band reserves in areas undergoing urban development would not be permitted to impede economic and infrastructural growth. As a result of this change in Federal legislation, the Papaschase Reserve was not established in the Edmonton municipality and the band’s traditional lands were sequestered by the city.

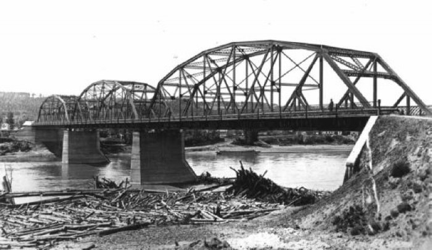

In 1912, just one year after this amendment, the construction of the Walterdale Bridge commenced. Replacing the Ross Flats ferry service run by John Walter, the bridge allowed for residents, merchants and traders within the Rossdale area to cross the river at their leisure. Following the 1911 amendment to the Indian Act, the old Walterdale Bridge was constructed during a moment in which the new city of Edmonton was able to dismiss the Papaschase Band’s constitutional rights in order to focus on infrastructural development. The needs of the Papaschase, in other words, held no sway over the needs of the larger city of Edmonton. Due to Edmonton’s growing population, crossing the North Saskatchewan needed to be easier and more efficient for Edmontonians; the fact that the bridge would cross over the Fort Edmonton Cemetery and Burial ground was no longer an issue the city’s early planners needed to address. The Walterdale Bridge is thus symbolic of this history of living together in this larger moment of transition, but under the divisive forces of a not so distant colonial system.

But despite this relatively recent history, these details of the Rossdale area’s development were hardly common knowledge to motorists crossing the Walterdale Bridge in the late 1990s. By this point, Rossdale had transformed from a low-income and isolated community of miners, artisans, and students to an affluent and gentrified neighbourhood of property owners. As most Edmontonians know, Rossdale is also home to a segment of the city’s river valley trail system as well as the recently closed EPCOR power plant. Prior to its closure 2009, EPCOR made plans to expand and update its old generation plant constructed in the mid-twentieth century. In 1999, EPCOR announced that the new power plant would house energy efficient and environmentally friendly machinery so as to create a more sustainable energy facility. Rossdale residents opposed the plan, however, out of concern for the historical value of the building as well as the recreational value of the trails surrounding the old plant; the community banded together to lobby against EPCOR’s plans for the sake of preserving the residential integrity of the river valley. In a 2004 paper, University of Alberta scholar Heather Zwicker pointed out that the dispute was driven by the question: “Should the city modernize its utilities or conserve its history?” But, as Zwicker explained, this difficult quandary was dismissed quite abruptly when EPCOR’s archeologists unearthed human remains proving that a 19th century burial ground laid the foundations for the power plant and surrounding neighbourhood homes.

After this rediscovery of the Fort Edmonton Cemetery and Burial Grounds, EPCOR abandoned its plans for expansion. The company consulted with Rossdale community members, Edmonton city councilors as well as representatives of the Papaschase Band and together the parties decided that an official memorial should be erected on the site. But before such plans were seen through, a makeshift memorial of unmarked white crosses appeared between the northern point of the Walterdale Bridge and the old EPCOR plant. In her paper entitled: “Commemorating Colonial Conflict in Edmonton’s Rossdale,” Zwicker suggested that this act of commemoration was “a physical reminder that our colonial accounts are not settled” and reminded Edmontonians, “that history is not easily skipped over and that our development as a civic community is not simplistic, but laborious, time-consuming and multi-faceted.” The makeshift memorial surprised motorists, cyclists and pedestrians walking by, Zwicker recalled, and prompted them to contemplate the messy overlapping of Edmonton’s historical layers beneath the bike paths, concrete, and sod.

Today, the completed Rossdale memorial stands as a reminder of this history. While some have argued that the official memorial is less effective than the makeshift memorial of 2001, many Edmontonians also recognize that this site is a lingering testament to our city’s colonial past. The memorial is productive because it reminds its viewers that we, as Edmontonians, have inherited this complicated history of coexistence. Considering just a few moments of the Walterdale Bridge’s story, it becomes clear that the bridge is itself a similar site. During that brief moment when the new bridge is nearly completed and the old bridge still stands, our city will be confronted with another visible reminder that the streamlined design of Edmonton’s future remains bound to a persistent colonial past.

Cynthia Spring is a writer who lives in Edmonton.

Follow us on Twitter @SpectatorTrib