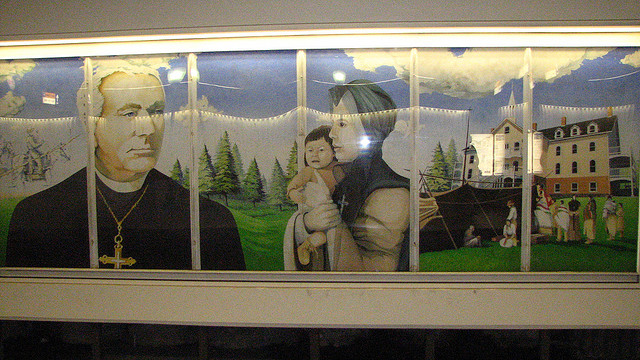

Like the thousands of Edmontonians that ride the LRT everyday, I pass by the Grandin Mural on a regular basis. And, despite its familiarity, the mural troubles me each time I encounter it. Located on the platform of the Grandin/government LRT station since 1990, the mural was commissioned by the French Association of Alberta and presented to the city as a gift. The mural, which depicts Bishop Grandin’s role in the institutionalization of Catholic missions, hospitals and residential schools in Alberta, has become the target of public criticism (most notably seen in several letters to the editor in the Edmonton Journal, starting in 2011).

Many ETS riders find the mural offensive insofar as it celebrates the charity of the residential schools system without acknowledging the well-known atrocities these institutions inflicted upon Canada’s Indigenous peoples. Despite the French Association’s philanthropy, and muralist Sylvie Nadeau’s generous representation of a significant historical figure in Alberta, the mural disregards any alternative historical perspectives that might question the legacy of European settlement.

[related_content slugs=”counting-our-dimes-public-transit-and-private-hockey-in-edmonton,the-walterdale-bridge-a-makeshift-memorial-to-edmontons-colonial-past,corporate-influence-and-aboriginal-consent-in-alberta-bill-c-45,full-time-kindergarten-in-alberta-is-a-womens-issue” description=”More from Cynthia Spring” position=”right”]

This benevolent representation of the early residential school system—a “civilizing project” that promised to culturally assimilate, enfranchise, and eventually deny Canada’s Indigenous peoples of their constitutional treaty rights—is, for many Edmontonians, simply unacceptable. And yet, the mural has been defended on the grounds that it is a celebration not only of the gentle Bishop Grandin’s great accomplishments, but also of the possibility of nourishing mutual respect within Edmonton’s diverse communities. But perhaps the most discomforting aspect, at least for me, is that the mural, like the ‘caring’ residential schools, has been inherited as an act of charity. To welcome the mural’s presence is to passively accept this legacy of paternalism that Edmonton, like all of Canada, has inherited.

Today, the Grandin Mural appears as an anomaly in Edmonton. Similar large public murals dubbed by the city as “The Giants of Edmonton” have appeared throughout the city over the past few years. These murals range from powerful representations of historical figures, such as the “Famous Five Mural” that depicts Canadian feminist activists Emily Murphy, Irene Parlby, Louise McKinney, Henrietta Muir Edwards, and Nellie McClung, to celebrations of cultural diversity, such as the murals painted throughout the McCauley neighbourhood by at-risk youth. Unlike the Grandin Mural, these pieces have been commissioned by the city as part of Edmonton’s Capital Clean Up program. Rather than simply painting over vandalism, local non-profit community agencies can receive municipal funding to replace unauthorized public art (or graffiti) with commissioned murals. The city’s primary motivation for the Graffiti Management Program is to preserve the integrity of public and private property throughout the city—values supposedly not respected by graffiti artists seeking to challenge such conceptions of ownership and taste. Despite the city’s narrow understanding of the artistic and political merit of graffiti, the project has received public support because it encourages community engagement with public spaces and celebrates the historical processes of community development throughout the city and province.

The Grandin Mural differs form these newer murals insofar as it openly celebrates the legacy of colonialism. In the first panel on the left, a Grey Nun holds a small Indigenous child while Bishop Grandin looks off into, to quote the plaque accompanying the mural, the “vast wilderness” of the Canadian West. In the background is a small group of faceless Indigenous peoples, being ushered into a tent by another clergy person. While the image of the child in the nun’s arms has clear associations with the residential school system, the building in the background is not, according to Juliette Champaign in her 2011 letter to the editor of the Edmonton Journal, a residential school. The scene actually takes place in front of a hospital/orphanage, demonstrating Grandin’s role in the larger infrastructural development of the west. The first panel thus suggests that through the construction of schools, churches and hospitals, Grandin was able to help transform this wilderness into a “land of emerging prosperity.”

The second panel depicts the early stages of Grandin’s developmental project. From the perspective of a trader on a boat, the second panel shows a grouping of both Indigenous and European structures near the edge of the North Saskatchewan River. The steep bank and the white convent (which resembles the Grey Nun residence in St. Albert) suggest that the scene is taking place near the developing and diverse settlement of Fort Edmonton. The train moving into the frame from the previous mural emphasizes the early Canadian project of national development across the country.

From this moment, the third panel makes a jarring jump to the present. Three adults join two children in a playground. In the background stand St. Joseph’s Basilica (Anglican), St. Joachim Church (Catholic) and Grandin Catholic Elementary School, notable structures surrounding the Grandin station. As many readers of the mural have pointed out, one of the playing children appears to be Indigenous; the absence of the crucifix around the child’s neck subtly distinguishes the child from the rest of the characters who all wear small crosses. The Indigenous child remains, like her ancestors in the first and second panel, an individual receiving the necessary education and charity from white caregivers. The Grandin Mural thus openly celebrates the legacy of the residential schools—institutions that intended to educated and protect young Indigenous Canadians from “the whiteman’s political institutions,” but inevitably functioned as a form of cultural assimilation and oversaw generations of racialized abuse.

My reading of the mural as a celebration of cultural assimilation might suggest that the mural should be removed, especially when Grandin Station connects commuters to Alberta’s government buildings and legislature. Simply taking down or painting over the mural, however, would only conceal the reality of Edmonton’s past. In response to similar criticism of the Rutherford Library’s Glyde Mural, the University of Alberta purchased Alex Janvier’s (Dene Suline/Saulteaux) large canvas “Skytalk” to counter the inaccurate representation of the peaceful and noble European settlement of Fort Edmonton. While the University intended to provide a critical response to Glyde’s interpretation of the past by commissioning Skytalk, the Janvier piece is now responsible for answering to this monolithic representation of European settlement. In this case, hanging a counter image to a mural like the University’s might only perpetuate colonial oppositions between Indigenous and non-Indigenous histories rather than disrupt them. Responding to the similarly exclusive Grandin Mural, then, becomes a difficult task.

In defense of her art, muralist Sylvie Nadeau wrote: “This mural is about love, compassion, learning to live and build in harmony together, through mistakes if we must, a future that respects us all.” In other words, the Grandin Mural is supposed to be about respecting the past in the ongoing struggle for coexistence between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities as well as between French and English settlers. The third panel clearly emphasizes this hope for the possibility of multicultural harmony: the Anglican and Catholic Churches stand side by side, and the white child constructively shares his knowledge and inheritances with the Indigenous child in the form of a toy building block. Similar to more recent murals like “The World on Whyte,” Nadeau’s mural celebrates diversity and culture in Edmonton. But unlike the Giants of Edmonton, the Grandin Mural openly acknowledges the history of this project of cultural incorporation. While the city paints over graffiti in an attempt to establish Edmonton as a culturally vibrant urban centre, the Grandin Mural illuminates the historical roots of liberal pluralism. Regardless of its intentions, then, the Grandin Mural provokes a powerful criticism of Canadian multiculturalism: contemporary cultural assimilation persists, intentionally or unintentionally, under the guise of cultural diversity.

—

Cynthia Spring is a writer living in Edmonton.

Follow us on Twitter @SpectatorTrib