A couple of years ago, an Anglican priest turned to his congregation, told them he wanted time off to write a book about jazz legend John Coltrane’s musical quest for the divine, and would they mind?

The unanimous response from the assembly of artists, songwriters and veteran rock’n’rollers that gather at St. Benedict’s Table on Sunday nights: “Cool.”

That was the blessing that took Rev. Jamie Howison from the pulpit on the corner of Winnipeg’s Broadway Avenue, to a joyful black church in Harlem. Perhaps some flocks may have been more skeptical about the pursuit, but Howison has cultivated a congregation immersed in art. “We’re not afraid to think, and ask questions,” Howison says, sipping coffee in an Exchange cafe. “I think it’s giving permission to people to let their imaginations open up.”

And for years, Howison’s imagination was stuck on Coltrane.

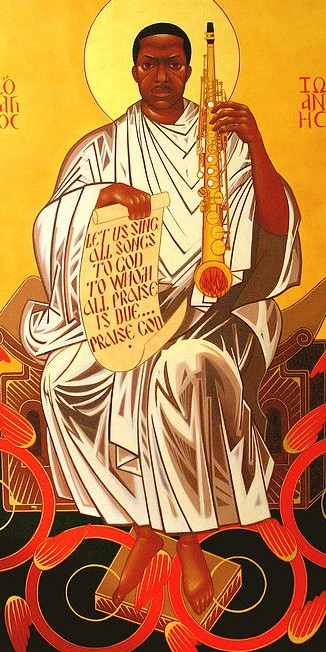

Now, the result of that fascination: Howison’s brand-new book, God’s Mind In That Music, is the culmination of years of study on faith, jazz and how Coltrane played each from the heart. In fact, he played faith so intensely that one young couple saw him live in 1965, were inspired to start a church, and made Trane their patron saint.

While the book delves deep into Bible tradition, it isn’t strictly a religious read: blogger Pat Loughery called it “a fascinating read for theologians who do not care for Coltrane, as well as for Coltrane fans who do not care for theology.”

Essentially, it’s a book for — and by — the consummate fan. Chapter by chapter, Howison immerses himself in eight of Coltrane’s songs, musing on the theology he hears in the arrangements each one at a time: embracing the music is so essential to the book, he’s written a listening guide.

At 52, Howison is not a musician — “all I play is the stereo,” he says — he fell in love with the rock’n’roll of the 1970s when he was just a boy. His musical tastes evolved s the decades grew, until about 18 years ago he discovered the Miles Davis classic, Kind of Blue. “That album is the gateway drug for lots of people,” he says. “That was it for me (with jazz).”

Before long, he was praying with the stereo on — which brings us to the story of how God’s Mind In That Music came about.

In 2008, Howison joined a writing retreat for pastors. At first, he was at a loss for a topic; he wound up churning out a paper on Coltrane’s tune “The Father and the Son and the Holy Ghost,” drawing out the feeling of faith in the sounds that he heard. After that, “I couldn’t stop,” Howison says. “It was, ‘I can go deeper. I know there’s more.”

And so he did. In January 2011, with his congregation’s blessing and a study-leave grant from an American foundation, he decamped from Winnipeg to New York City, where he worked at Columbia University’s Union Seminary and plunged into its vast jazz library. And he went to a ton of shows: 15 jazz shows in 30 nights, many at dark little clubs nestled off Manhattan’s jostling streets.

And he talked about Coltrane, to anyone who would listen.

——

ST: When you talk about exploring theological truths in Coltrane’s music, can you highlight a specific case?

One of the easiest ones to access is a piece called “Alabama.” It was recorded two months after the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist church in Birmingham, Alabama. Two months after this bombing, Coltrane took his great quartet into the studio, and recorded one of his shorter pieces. It starts out as a lament, all you hear is the trembling of the pianist’s hands on the piano. And Coltrane starts to play, and it almost sounds like he’s speaking: there’s some speculation he was playing the text of Martin Luther King’s funeral speech for those little girls. Then it swings into the blues, does that for a minute and a half. Then dead silence, and it returns to the lament but this time, there’s more strength. There’s more resolve. The lament becomes this statement of resilience.

It’s actually a brilliant expression of the Biblical tradition of lament: in the psalms, where they often begin with loss and sorrow, and through something like the blues begin to move to this place of strength and resilience. It’s just such a powerful piece of music, and that’s how I hear it. So I bring it into a dialogue with the tradition of psalms.

ST: When you started talking with jazz fans, scholars and theologians about what you were working on, what were the responses?

One was people who instantly got it, and jumped in. Others were hesitant. Coltrane’s primary biographer, Lewis Porter, he was a little bit reticent. He was kind of like: Coltrane didn’t say that much about what he was thinking or believing; you’ve got to be really careful about presuming to know too much about somebody who is dead. And I said, “that’s not really the project. The project is more my listening to what’s going on in his music, in the context of his life and that culture.” He sat a great interview for me.

ST: How do you bridge that gap, between what Coltrane left unsaid to what you hear?

He did say more, I think, than Lewis Porter is prepared to acknowledge. Time and again (Coltrane) does speak about either his religious roots, or in retrospect his struggle with heroin and alcohol. Then his liner notes and the poem that are a part of the album A Love Supreme, he just lays it out. And so with that much as a starting point, and the fact that he said after A Love Supreme on — so from the end of 1964 through ’til his death in ’67 — he said everything he was doing, musically, was prayer. That gives you permission to hear the music that way. Still, I was careful. In the book I say very clearly: “I’m listening. This is what I’m hearing.”

ST: You selected eight of Coltrane’s pieces to focus that listening on. Why those eight?

Some of them are obvious, they just jumped out as pieces that he was very intentionally using to express his beliefs, his searching. The whole Love Supreme album is, it just is, a prayer. That was a no-brainer. “Ascenscion,” in its own way — it’s such a controversial record, I couldn’t not write about it. The other things were a little more, “okay, this makes sense, this is what I’m hearing in this.” So it was a case of careful listening of that period in the last eight years of his life.

ST: Sometimes, engaging theological discussions can be foreign to people. What is the value for them in exploring it in this way?

It simply is part of the story of this music. So many of these (jazz musicians) came out of the church, even if they ended up in a different place ultimately. The other thing is… singer-songwriter Alana Levandoski made the observation years ago that so many people she hangs out with in the music business — who wouldn’t for a minute dream of walking through the doors of a church — as soon as the first pint is swallowed, are wanting to talk about God. Wanting to talk about life meaning. Wanting to talk about things spiritual. Well, that says there is some interest out there. I hope in a fairly open and non-pushy way, I invite that conversation.

—-

Before going to New York, Howison consulted with some top scholars of jazz and blues. One fear: could a white guy from Canada come into the black American culture that gave birth to jazz and understand it true? The advice he received: yes, but you have to go to church. Not the big tourist churches, but the little churches in Harlem where “real people are.” So that’s exactly what Howison did.

—-

ST: Did your research take you anywhere that surprised you?

One of those churches in particular — it was called the Greater Good Memorial African Zionist Episcopal Church — was fantastic, both in their embrace of me and in their demonstrating the connection between black preaching, gospel music and improvisation. Scorching preacher. When he started to go, it was all about the cadence of his voice, and the congregation’s call and response, back and forth, the energy. It was like seeing great improvisational jazz in a club, where the audience’s response drives the musicians higher. Same thing. That was a real “ah-ha” moment. I read about it, but to be there, that was crazy. That’s a different world of the church.

ST: What do you hope people take away from God’s Mind In That Music?

My big hope is that this becomes part of an ongoing conversation around the life and music of Coltrane. It’s incredible, the interest that’s out there. And I hope that this becomes a serious contribution to that conversation. For the more casual reader, just to come away with a sense that music matters. For me, that would be the best. Partly because we’re so surrounded by music all the time, I like the idea of people being invited to get excited about really listening again.

—————–

God’s Mind In That Music is available in hard-copy and Kindle format from Amazon.com, as well as Hull’s and McNally Robinson bookstores in Winnipeg and Crux Books at Toronto’s Wycliffe College.