A startling number of Winnipeggers suffer from perimeteritis, which is defined — by the Encyclopedia of Manitoba, no less — as an affliction that inhibits ‘peg-dwellers from crossing the Perimeter Highway, and, “in extreme cases prevents them from even recognizing that life exists outside of the boundaries of the City of Winnipeg.”

The far reaching consequences of this disease is that Winnipeggers begin to see all of Manitoba as a wonky blend of boomtown nostalgia, moderate politics, disillusioned hipsters, and suburban sprawl. They forget that while the Perimeter Highway may envelop about 60 per cent of the province’s population, it only captures one per cent of its area. They don’t see how the geography found beyond city limits, from prairie to parkland to forest, interacts with its respective communities to form dynamics very different from what is found in the capital.

[related_content slugs=”honey-nazis-and-the-manitoban-identity” position=”right”]

The real tragedy here, however, is not just in Winnipeggers’ constrained understanding of what makes this province what it is, but that they are missing out on the gems of stories found all over rural and small town ‘toba. This city might think it has enough of its own yarns, tales, legends and myths to keep the fireside chat thriving, but c’mon: isn’t the General Strike of 1919 and the ever-changing fate of downtown becoming tired themes in the overall plot? For a bit of unexpected pizazz, and a potential ointment for perimeteritis, Winnipeggers should look beyond the great W into the universe beyond. And, for example, they might find a little town called Plum Coulee.

Plum Coulee lies between Winkler and highway 75. Nestled in Manitoba’s Bible Belt, its seven hundred odd residents enjoy a quiet lifestyle that comes with summer excursions on their own lake, evening strolls to Annajo’s Bistro (one of the best homestyle restaurant joints around), and the happy knowledge that they sit on one of the few places in the province that is actually true prairie. But under the peaceful veneer of the August plum festivals and fall perogie suppers, Winnipeggers will find the sort of story that’ll intrigue them right out of any -itises they might be suffering from. Buried in the history of Plum Coulee lies the remains of John Larry “Bloody Jack” Krafchenko.

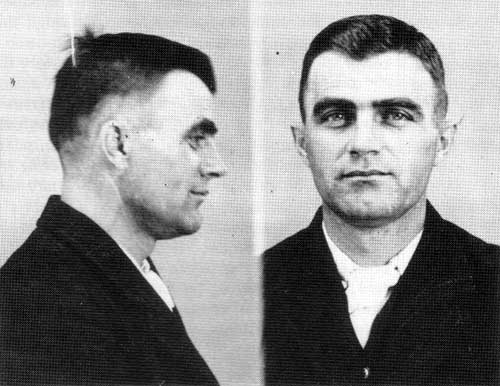

Born in Romania, Bloody Jack grew up in Plum Coulee around the same time that the first Russian Mennonites started to arrive in the town, a migration sparked by the Canadian Pacific Railway’s arrival in 1884. But Jack differed dramatically from the pacifist neighbours who had come to carve out a faith-based community in a new land. No doubt taking the cue from his father, a gambler and carouser of a man, and his mother, whose bout of horse thievery in Europe had become stuff of legend, Jack robbed his first jewelry store at the age of eleven. Four years later he spent time in jail for stealing a bicycle. But these petty crimes were mere warm-ups to the roller coaster that was to come.

Jack’s adult years hint at an enigma of a man. His legacy flirts with, but does not quite fit, the cliched Robin Hood-charm of other notorious bandits. He had charisma to be sure, wielding a defiant spirit to great acclaim from Manitoba’s most alienated immigrant communities, and his wide travels — including a stint of professional wrestling in the United States and Australia — came with a fluency in five languages. But he also traveled the Prairies to promote….prohibition. That’s right, our hero is like that guy from the Dos Equis commercials, only without the beer.

The movie of Bloody Jack’s life would have to tinge a Jesse James-like theme with Laurel and Hardy-like slapstick. After being arrested in Saskatchewan for financing his prohibition tour with fraudulent cheques, Krafchenko busted out of the Prince Albert Penitentiary by whacking a prison guard over the head with a paint can. From there he cut the prohibition tour short to kickstart a crime spree that ran throughout North America and culminated in Europe. He made it across the pond by hiding in an Atlantic freighter. In Milan, he casually joined a group of onlookers observing a police investigation of a bank he had just robbed.

It was love that brought Jack home, and it was home that ultimately sealed his fate. Married in 1905, he decided to take his new bride back to tranquil Plum Coulee. You know, settle down, raise some kids, retire in peace. Or, alternatively, begin North American Crime Spree 2.0, and leave the spouse to, well, tend to the plum festivals and such. Like many Manitobans, however, Jack’s irrepressible urge to leave this place was immediately replaced by an irrepressible urge to return once he had left. Krafchenko came home and — after testifying at a friend’s murder trial, getting arrested for various crimes, and serving jail time — he persuaded the Winnipeg police that his particular expertise would be very useful as a ‘robbery consultant.’ He also persuaded them that he should be paid upfront. He took the cash and ran. To Ontario (blech).

Jack left Ontario because he was fired from a misguided attempt at an honest job on the railway. Or he left because, well, you know, it was Ontario. Either way, Plum Coulee had beckoned again. Reconciling himself to the fact that he was home to stay left his insatiable drive for adventurous thievery only one option: he would rob the Plum Coulee bank. Now, the little town had always served Krafchenko well, had always provided snippets of peace inbetween bouts of lawlessness. Turning his criminal mind onto the town that had, in a way, sustained him, was his fatal misstep.

When Plum Coulee bank manager Henry Arnold saw Bloody Jack dash out of the front doors with wads of cash he did what any small town ‘toba bank manager of the time would do; he chased after him. In this moment Krafchenko, perhaps in the heightened intensity of committing this crime on a street he had walked as a child, ignored his usual policy of brains before violence. He turned around and shot Arnold dead. The murder led to a prompt investigation and even prompter arrest. It was the just end to Jack’s many adventures. Kind of.

Bloody Jack convinced his lawyer and some police officers to help him organize an escape from jail. After dropping thirty feet from a prison window, he skulked around the North End in various disguises until he was finally recaptured and put in a cage on Vaughan Street. His trial was held outside the city — no perimeteritis for Jack — in the town of Morden, twenty-five kilometres west of his hometown. Legend has it that his conviction for the murder of Henry Arnold saw tens of thousands petition the province for reconsideration. More sobre accounts note that supporters asked the federal government for clemency. His personality and daring feats, despite their questionable nature, had obviously entered the hearts of some.

On the morning of July 9th, 1914, John Larry Krafchenko was hanged at Winnipeg’s Vaughan Street Jail. Some reports describe his mother attempting several times to revive his body, performing mouth-to-mouth resuscitation herself, and that the gun he used on Arnold is still held by the Winnipeg police department.

All that to say that the world turns outside the Peg’s borders. Some stories profoundly describe the mini-political cultures that have evolved in different regions of the province while others, like this one, simply add an intriguing storyline to the province’s idea of itself. It’d be a shame if Winnipeggers stuck only to the story lines they find within the Perimeter.

__

Johanu Botha is a student of public policy and political philosophy. His hobbies include the mandolin and intermittent bouts of existential angst. You can reach him at johanu.botha@mail.mcgill.ca