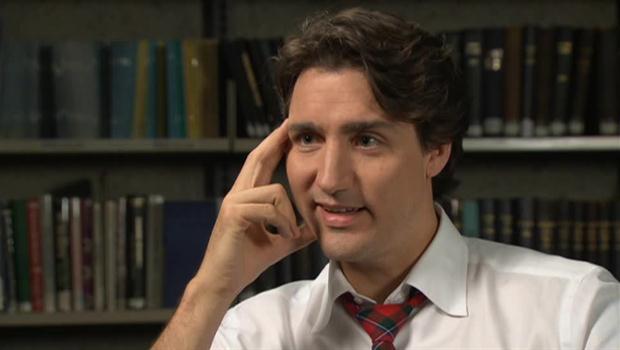

From the time the Tory attack ads against Justin Trudeau—ads that rightly questioned whether he had the judgement and experience to be prime minister—fell flat among the electorate, the Conservative Party has been hurling modest improprieties at the young leader with the hope that something, anything, will stick.

The harmless “root causes” musing on the Boston bombings and the speaker fee “controversy” were non-issues. The Tories should have stuck with what could be the defining question of the next couple years: whether a man with virtually no political, let alone professional, experience has the ability to lead the nation.

Given the propensity of Canadians to overlook his flaws, it has been an ongoing struggle for both the government and the Official Opposition to interpret, or respond to, Justin Trudeau as leader of the Liberal Party of Canada. One thing, however, is just as evident as it was upon his election in 2008 in Papineau: to compare Pierre Elliot Trudeau, a charismatic Quebec public intellectual and 14-year prime minister, with his charismatic eldest son is to miss the forest for the trees.

By his own admission, Justin Trudeau is not an intellectual. His policy positions, when articulated, are typically vague or incoherent, or a combination of the two.

Perhaps this could be disregarded on the basis of an impressive resume. Most politicians lack the intellectual rigour of Pierre Trudeau. Some are, in fact, brazenly suspicious of intellectualism and academia. But these politicians have instead made their electoral case on the basis of managerial competence; brandishing a professional record, in business or law or politics, to back it up.

Justin Trudeau has worked briefly as a high school teacher. He has never worked a dead end job and never run a business. Nor is he a career politician. For all intents and purposes, he has never had much of a career at all, nor has he used his life the way his father did: as an iconoclast, a writer and an activist integral to Quebec’s Quiet Revolution before being elected leader in 1968.

When Martha Hall Findlay, a candidate for the Liberal leadership, spoke at the party’s April convention, she made a statement almost entirely missed by the national media.

In what was surely an attempt to boost her spirits and those of her supporters in the face of a foregone conclusion, Hall Findlay made reference to the fact that 40 years earlier, on the same date in 1968, Grits had elected an underdog as leader and prime minister. Although Pierre Trudeau led throughout the convention, he did not push above the 50 per cent mark until the fourth and final ballot amid a talented field of candidates, virtually all of whom were cabinet ministers in Lester Pearson’s government.

Despite the practical purpose of her statement, Hall Findlay was sending another message, albeit implicitly: that competition is what makes a healthy political party and that the Liberals, by embracing hereditary rule and borderline demagoguery, would become a cult of personality.

Trudeau the father, after a long intellectual life and tough convention, had earned his charisma. Trudeau the son, catapulted to the leadership after one ballot with nearly 80 per cent support, seemed only to possess it by osmosis.

It would seem that this political charisma is the only important leadership criterion for modern Liberals. It is the only discernible reason they compare father and son. It is also seemingly the only reason, besides the feeble defence that Justin “grew up around politics,” that they elected him at all.

In short, despite Tory attack ads fizzling out, the party is right to bring up these issues. In several respects, the Conservative Party is the only organization that has spoken frankly about the flaws of Canada’s “natural governing party.”

They should keep doing so.

If Justin Trudeau were named Justin Smith, he would not have been a contender for leadership, let alone the leader of the third party on track to a majority. Indeed, the most disturbing aspect of Justin Trudeau’s leadership is the profound sense of entitlement at the centre of it.

The privileged attitude of Justin essentially inheriting the party. The deluded feeling by the membership that they are repeating history. The palpable, almost defeatist, attitude of the electorate who believe there is something inevitable about another Prime Minister Trudeau.

It influences the way in which Justin now conducts himself, with swagger and confidence. He speaks, and many have pointed this out, like an actor playing a politician.

What is troubling, though, is that one gets the sense there is nothing more than an actor in Justin.

All politicians act. They dumb their positions down for the electorate. They stay on message. But even the best political phonies break character periodically, letting slip some wonkish response or long, thoughtful analysis not yet focus group tested.

But Trudeau never has, unless it was to utter some bumbling and divisive statement on Quebec or Alberta’s place in Canada.

Beyond the vapid talking points and cliched platitudes, we get the sense there is nothing else he has to say. And, even more problematic, no other principled or thoughtful reason for entering politics in the first place.

We have now spent quite some time with Justin Trudeau. Ask yourself what distinguishes him, in terms of public policy positions, from Michael Ignatieff (the man who reduced the Liberals to 34 seats in the House of Commons) and, if you are honest, you will surely answer “almost nothing.”

Indeed, Ignatieff, who lost in part because of regurgitated Liberal policy from the 1990s (national day care spaces, anyone?), presented himself as an old-school, equal opportunity Liberal. Equal opportunity in the traditional sense of a Grit leader: campaign from the left, govern from the right.

It is how the Liberals vilified the FTA, NAFTA and the GST before somehow becoming the champions of trade and smart taxation. It is how Ignatieff supported the War in Iraq, then didn’t, and wrote an explosive article defending torture before realizing Canadians find such ideas distasteful.

Trudeau holds almost the same values, economic views and policy positions as Ignatieff, only without the burden of having had any thoughtful principles to shed for electoral gain.

We need to “grow the middle class.” We need “more trade.” And our institutions should be made “more transparent.” How? Not sure on the middle class or trade, but Grits believe we can fix Parliament by appointing better senators, incorporating more digital elements and tweaking ethical rules.

This is the kind of weak soup that led Ignatieff to desperately yell “Rise Up Canada!” during the 2011 campaign in reference to a song by Bruce Springsteen. Ironically, we all know The Boss was famous for another tune called “Born in the U.S.A.”

The Conservative Party of Canada has deep problems and has done a great disservice to the institutions of Parliament time and again. But overall, the Tories are right about Justin Trudeau.

___

Ethan Cabel writes for the Spectator Tribune. Follow him at: @ethancabel1

Follow us on Twitter: @SpectatorTrib