[related_content slugs=”night-on-the-towne,are-we-warm-yet,jets-flying-on-a-wing-and-our-prayers” description=”More by Ross McCannell” position=”right”]

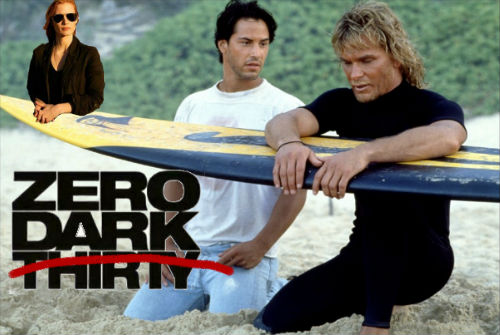

It’s hard to imagine now, but back in 1991 director Kathryn Bigelow’s brilliant Point Break was snubbed at the Oscars. Her bank-heist soul-search surf classic wasn’t even nominated.

The Academy isn’t ignoring this franchise in 2013 though, as Point Break’s long-awaited sequel Zero Dark Thirty goes into Sunday evening as one of the favorites for best picture. But is Zero Dark Thirty really worthy of this recognition, or is praise being heaped on the sequel in an attempt to make up for the tragic overlook of yesteryear? Also, why did Bigelow call it Zero Dark Thirty? Is “Dark Thirty” code for Swayze? If so, the film is at least factually accurate: it has zero Swayzes.

The plot of Point Break has now become one of the canonical mythological journeys of our human culture, but I’ll recap it in case an alien race is decoding this webpage out of some stray cosmic radiation. Keanu Reeves plays Johnny Utah, a rookie FBI agent who infiltrates a gang of surfer dudes who rob banks to fund their never ending pursuit of the ultimate ride. Patrick Swayze plays Bodhi, the alpha male of this pack, a charismatic guru of zen ocean enlightenment. His ex-girlfriend describes him as “a modern savage… a real searcher.” Bodhi serves as both antagonist and bromantic interest for Johnny, who must choose between bringing Bodhi in to face the law of the land and adopting Bodhi’s vision of a higher cosmic law.

Zero Dark Thirty picks up in 2003 with a new protagonist: Maya, a CIA rather than FBI agent. Bigelow chooses not to import any of the original characters; this film is principally a spiritual successor. The name Maya itself a strong show of the line of spiritual succession. “Maya,” like “Bodhi,” is a name with spiritual meaning. Google it. Crazy, right? It’s as though the synthesis of Johnny Utah and Bodhi that’s achieved at the end of Point Break (on a beach in Australia when Johnny lets Bodhi out of his handcuffs to sacrifice himself on earth’s biggest wave and then tosses his own FBI badge into the water as he walks away) is reborn in Maya. But Maya isn’t after surfing bank robbers. She’s after Osama Bin Laden. Osama don’t surf.

At its core, every Kathryn Bigelow film is a pseudophilosophical study of the question: “to bro or not to bro?” Just like Johnny Utah, and every other Bigelow protagonist, Maya is a bro fighting to be a bro in a hyper-bro world. The difference is that Maya is already the ultimate bro at the start of the film. Johnny Utah was a bro, but he needed to learn and then practice the teachings of Bodhi’s cosmic broness in order to apprehend him.

During his first attempt at surfing, Johnny Utah says, seemingly for no reason, “I’m Johnny Utah!” to which a 15-year-old surfer kid immediately responds: “Who cares?” Johnny has a lot to learn. But in Zero Dark Thirty, when the CIA director has just inspected the model of what Maya believes to be Osama’s house and then asks Maya who she is, she says “I’m the motherf&%$er that found this place sir.” That’s right: she refers to herself as a “motherf&%$er.” She has nothing to learn.

When a protagonist has nothing to learn it’s a problem for a film, because it means we don’t have much to watch. In Point Break we watch the evolution of Johnny’s broness. During an early surfing sequence Johnny blurts “I gotta be crazy!” to which Bodhi counter-offers “But are you crazy enough?” And so later in the film, Johnny understands that he must jump out of an airplane without a parachute, free-fall tackle Bodhi in mid-air and hold a gun to his head. That’s drama.

By contrast, Zero Dark Thirty is a little light on drama. The plot of Zero Dark Thirty is: Maya starts off as a super-bro who thinks she knows stuff, and then she’s proved right. The end.

Like most sequels, Zero Dark Thirty is a weaker piece of film art than the original. It just doesn’t have the same weighty ideas at work as its predecessor. Point Break was about making meaningful choices between subtle though significant differences in varieties of Broness. Zero Dark Thirty is about being stubbornly a bro when you think you know what you know.

Johnny faced serious decisions like: do I shoot the man of my bromatic dreams, or yell at the sky as I fire my whole clip into it? Maya just participates in a long series of scenes that reiterate the fact that she’s more bro than everyone she works with. During one meeting, her co-workers all respond to a yes-or-no question with things like “a weak 60 per cent he’s there” until she frustratedly states: “It’s 100 per cent. Okay, 95 per cent, because I know certainty freaks you guys out. But it’s 100.”

In the same way Ingmar Bergman’s cinema spirals out elegantly from its central thematic concern with death, Bigelow’s cinema tactically raids us with its prioritized thematic concern with dudeness. But with Zero Dark Thirty, she may have exhausted her subject. You can’t help but think that maybe Point Break is one of those works of art that contain everything, and therefore there was nothing of substance left for Bigelow to work with in the follow-up. Point Break reached Shakespearean heights with its dialogue. Zero Dark Thirty mostly has the feel of an uninventive campfire story told by a dorky dad.

It’s not a bad film, but neither is it Oscar worthy. Does it really makes sense to reward Zero Dark Thirty just to make up for the sins committed against Point Break? I don’t know. Godfather II and Lord of the Rings: Return of the King are the only sequels ever to win best picture at the Oscars. Will Zero Dark Thirty join them on Sunday night? We’ll find out. I want to know why they didn’t just call it Point Break 2.

——-

Ross McCannell is a writer and tree-planter. He winters in Winnipeg. Follow him on Twitter @RossMcCannell.

——