It’s time to break with the pattern. So far in these articles I’ve been choosing sides, taking two things, reviewing one against the other and ultimately declaring a winner. I’ve enjoyed this and will no doubt return to it but this time, right off the hop, I’ll let you know that we’re doing things differently. This time we’re going to have nothing but winners.

Our winners come in a pair and are different in many ways. One is a movie and the other an album. One is the return engagement of a collaboration between two young artists on the rise, working together and finding a fuller realization of their voice. The other is the product of a veteran, a refinement of familiar themes by an established singer and songwriter.

The movie is Young Adult from director Jason Reitman and screenwriter Diablo Cody. The album is Charmer, the eighth studio release from Aimee Mann. So what correlation exists between this movie and that collection of songs? They demonstrate a primary concern with empathy over subtext, spotlight their creators as portraitists, and, for their trouble, provide their audiences with deep and valuable glimpses into the lives of others.

Young Adult came out in December 2011.

It had some hype around it as it was the second pairing of Reitman with Cody, who had previously worked together on the massively successful Juno, a movie that you likely know as the flick that unleashed Ellen Page onto the world or the flick that replaced Garden State as your less cool friend’s favourite movie. (As a side note, I have just reread that last sentence and agree that it is totally insufferable but still choose to stand by it and agree that this qualifier may have made things worse).

Young Adult never achieved the same monetary success as Juno, making just under $22 million on a $12 million budget as opposed to $231 million on a $7 million budget. It failed to fully penetrate its way into the mainstream consciousness and as a result received less critical attention, although most of the attention that it got was very positive, with the movie currently scoring a clean 80 per cent on Rotten Tomatoes. Juno, however, scores a glowing 94 per cent.

Despite its position as a less successful younger sibling, Young Adult is a far superior movie. It gives up on most of the fetishes that have marked Reitman and Cody’s other work, such as shocking the audience with silly twist endings (remember what happened when George Clooney’s character knocked on his lady’s door at the end of Up in the Air?) or self-satisfied impressionistic dialogue (Rainn Wilson and almost everyone else in Juno) while holding onto the strengths that gave that previous work its deserved credence, such as tremendous performances, casting, and complicated characters working their way along simple, relatable and inviting narrative threads. The movie is crisp and self-assured. It is mature even as it portrays the beautiful and disastrous complexity of a woman who is anything but.

While Reitman and Cody’s most famous work, Up in the Air and Juno, was content to colour competently and sometimes splendidly within the lines, Young Adult wants to do more. It wants to draw its own lines and doesn’t really care if you like them or approve. It makes bold choices with its story, characters and casting and showcases those choices by allowing its visual elements to remain perfectly simple.

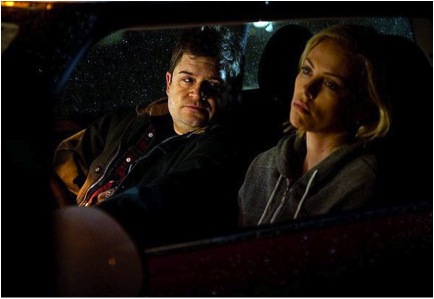

The greatest narrative choice made by Reitman, Cody and company is the choice to eschew the narrative in favour of its characters – especially its main character, Mavis Gary, played with perfect and cruel precision by Charlize Theron. You see, Young Adult isn’t a movie about a story, it’s a movie about Mavis. It’s a movie about one particular person and it’s main priority is not to weave a character into a story where the audience is asking “What happens next?” but rather to fully capture the vastness of this one entity so the audience will ask “Who is this lady?”

Every single scene, plot movement and character interaction is designed to better capture her, to draw different elements of her character out into the open, to reveal her. Young Adult is more of a portrait than a story; a detailed and character driven endeavor that doesn’t want to editorialize an opinion or thrill with a tale but only to allow its audience to fully understand one damaged and intolerable individual. Any learning that comes from that is encouraged but not really their concern. Their only concern is Mavis, because in Young Adult the character is the only story, the only message. The character is the movie.

Aimee Mann has been making music since 1985 when she and her band ‘Til Tuesday released their debut album, Voices Carry, and its title track became an early video hit for MTV.

Even from those early days when Mann was sharing the songwriting duties with three other bandmates, her tendency to write lyrics that seek to understand a single human subject rather than relating an autobiographical experience was clearly beginning to manifest. That tendency would continue to grow as she gained more control over the songwriting for ‘Til Tuesday and then expanded into her solo career. From tracks like “Mr. Harris” on her debut solo record, Whatever (1993) to the entirety of The Forgotten Arm (2005), a concept album about an alcoholic boxer and his lover who run away together after meeting at a state fair in the ‘70s, Mann has demonstrated an ability to write songs that are portraits. Her songs focus on single characters and mine their depths, excavate their souls.

Her latest record is called Charmer and its defining trait is its empathy.

Just like how Reitman and Cody manage to balance a narcissistic megalomaniac with a woman in crisis in their depiction of Mavis Grey, Mann is able to simultaneously revel in her characters’ flaws while celebrating their virtues. Songs like “Labrador” and “Gumby” reveal characters who are cold and exhausted, weak and losing but noble in their efforts; noble in their struggle against their own powerful human frailty. The monstrous and angry time bomb in “Gamma Ray,” the empty and lonely opportunist in “Red Flag Diver,” the self-loathing and titular “Charmer.” Each song is a portrait, built around a single character, and each song is principally dedicated to revealing that character’s soul fully, perhaps even painfully, but always kindly and without judgment, regardless of whatever darkness may lie within. Her cast of characters is a band of losers but each one is lovingly portrayed, lovingly painted into being.

Charmer and Young Adult are focused and unflinching portrayals of people. They both aspire to explore the depths of a single person, to bask in their weakness while never denying their goodness. They present us with stories that eschew the heroes-who-always-find-a-way in order to show us real people, people who may be more like us than we would like to admit. They are a representation of people who fail, and people who try in the ways that they can but are incapable of transcending to a higher plane of morality or strength. These are the people who resent those who love them for loving them or self-destruct at the pivotal moment. These are stories that understand us for being what we are. These are stories that don’t seek to inspire, they seek to forgive.

___

Theodore Wiebe is a writer living in Calgary. You can follow more of his important nonsense on Twitter: @TheodoreWiebe

Follow us on Twitter @SpectatorTrib