PART ONE: 1812-1911

[related_content slugs=”two-centuries-on-point-douglas-part-two-1912-2012″ description=”Part Two” position=”right”]

This year marks the 200th anniversary of the arrival the Scottish settlers who first established an agricultural colony on Point Douglas in 1812. Located along the Red River a couple of kilometres north of the Forks, Point Douglas would play an essential role not only in the history of the city of Winnipeg, but in the development of Western Canada.

Today, Point Douglas is one of Winnipeg’s most enigmatic neighbourhoods. To explain where it is to lifelong Winnipeggers can take some effort, to say nothing of having them navigate its jumbled, irregular grid of small streets for the first time. But even if many don’t where it is, there’s a dual perception, in Winnipeg’s collective consciousness, of what Point Douglas is: both a cesspool of crime and dysfunctional poverty, and a neighbourhood experiencing re-investment and a significant influx of new immigrants and hipster artist types. Neither perception is entirely wrong, and often, this duality is found on the same street. Within 200 feet of where Lord Selkirk’s settlers arrived, there are both new condo developments and the campsites of the homeless among the banks of the Red River.

This is a brief and selective timeline of the people, places, and events that helped shape the Point Douglas neighbourhood of today. In Part One, we explore the origins of a permanent agricultural settlement of Point Douglas, and its transition to a dynamic and cosmopolitan city neighbourhood.

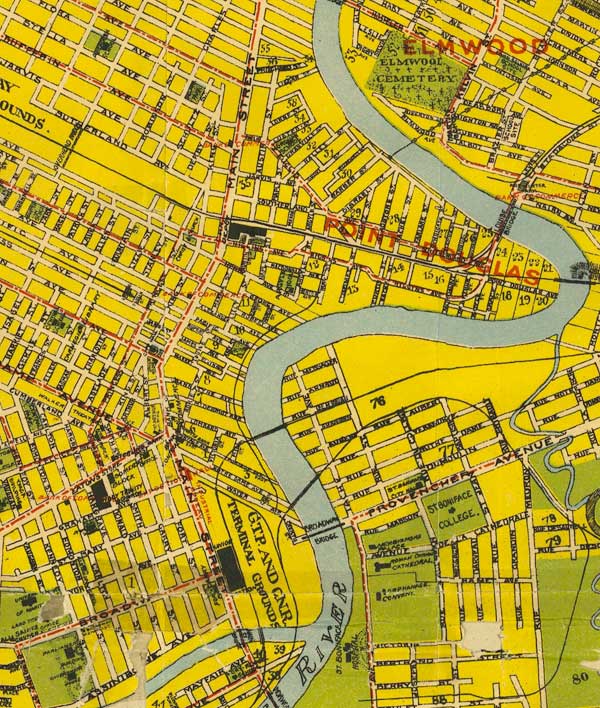

Point Douglas and its surroundings, as it appeared on a Winnipeg map from 1911

1812 – A band of a few dozen Scottish settlers land near what is now the corner of Waterfront Drive and Alexander Avenue. Here they build a small wooden stockade called Fort Douglas, and for the next several years attempt to establish an agricultural colony on the Red River. The colony is the idea of Scottish nobleman Thomas Douglas, Earl of Selkirk, who grants the land to the settlers and pays for their passage to Red River. Narrow farm lots are carved out on Point Douglas (named after colony’s benefactor), and north along the Red River. Owing to disastrous weather and simple bad luck, the isolated colonists are forced to spend the first few winters in what’s now Pembina, North Dakota, and depend on the generosity of the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Saulteaux chief Peguis to survive.

Added to the settler’s hardships on Point Douglas are increasing tensions between them and the local outpost of the North West Fur Trade Company. After several confrontations, including a gunfight near the Forks, tensions culminate in June of 1816, at the Battle of Seven Oaks (near what is today the corner of Main and Jefferson Avenue), which leaves 22 dead.

Waterfront Drive as it appeared in 1817

1826 – After several years of stability and peace in the Red River settlement, a flood in the spring of 1826 submerges nearly all of present-day Winnipeg. Colonists flee to higher ground at Bird’s Hill to wait out the flood, and one eyewitness recalls seeing at night, a farmhouse ablaze and floating down the swollen Red River.

The floodwaters wash away Fort Douglas, which had just been sold to Robert Logan the previous year. Together with his Saulteaux wife Mary, Logan builds a homestead and raises a family on the site of the old fort, including a windmill used by nearby farmers.

Logan’s mill, as it looked in the 1860s

1860 – Edmund Lorenzo Barber arrives at Red River from St. Paul, and is among a handful of young American and Upper Canadian men coming to set up business ventures in the growing colony. Many of these far-sighted (or simply crazy) entrepreneurs cluster around what became the corner of Portage and Main, but a few, including Barber, operate in Point Douglas. In 1863, at the site of the log house he would build on Euclid Avenue several years later, Barber opens a new store. With practically no street names or addresses, his advertisements direct potential customers to “Klyne’s Old Place, Point Douglas.”

Advertisement in the April 13, 1863 edition of The Nor’wester

1873 – Winnipeg incorporates as a city, and although it is inside the new City boundaries, Point Douglas is still considered its own village, which, except for a cluster of businesses on Main near Higgins, is still semi-rural. In the Spring of 1873, hundreds of Aboriginal people gather on Point Douglas to participate in a dog feast ceremony, which lasts for several days. This is the last time that such a large gathering of Aboriginal tribes occurs in Winnipeg, as urbanization and discriminatory by-laws will soon prohibit this.

Though the 1870s are a time of economic uncertainty for Winnipeg, steady urban growth continues, and public infrastructure rushes to catch up. In 1875, City Council votes to extend Lusted Avenue to the banks of Red River so that lumber that is floated up river can be brought into the city more easily. On George Avenue that same year, workmen uncovers a number of human skeletons, believed to be among the dead from Seven Oaks, who Chief Peguis and his men reportedly helped bury near Fort Douglas some 60 years before.

The beginnings of urbanism: rowhouses built on Henry Avenue in 1872

1881 – The Canadian Pacific Railway cancel their plan for Canada’s first transcontinental line to cross the Red River at Selkirk, and instead route it through Point Douglas after Winnipeg’s City Council lures them by paying for the construction of a bridge, and exempting them from property taxes. The railway runs down Point Douglas Avenue, which in the early part of the century was laid out as an access road for Point Douglas farmers. Now, it becomes the route of the railway that grain farmers use to send their crop east to the markets of the world.

The arrival of the railway shifts the city’s fledgling industrial and warehousing activity from the steamboat landings near the Forks, to along either side of the tracks in Point Douglas. The railway also kickstarts a massive real estate boom throughout the city, which sees the subdivision and selling off of nearly all of Point Douglas’ remaining farm lots that dated back to the Selkirk settlement. (Today, most of the streets in Point Douglas follow the property lines of these of these ancient farm lots.)

The original CP railway station on Main Street near Higgins Avenue.

1889 – The 1880s see the beginnings of spatial class distinctions in Winnipeg, as the south end becomes home to the city’s growing wealthy classes, while the north and central areas becomes identified with the working classes and the countless numbers of poor immigrants pouring into the city.

In Point Douglas, the lines between classes continue to remain blurred, with a number of merchants and professionals living alongside labourers and tradespeople. Premier John Norquay, Manitoba’s first and only premier of Metis ancestry, moved to a large duplex on Hallet Street in the mid-1880s. After a change in government in 1888, Norquay continues to serve as the leader of the Official Opposition, until he dies suddenly in his home on Hallet Street one morning in July of 1889. Shortly after, his widow, Elizabeth Setter, moves to a house across the street, and remains there until the early 1900s.

“Honest John” Norquay

1909 – Edmund Barber, one of the oldest residents in Point Douglas, dies in his log home he built on Euclid Avenue in the 1860s. After nearly half a century, the old house is now tucked away from an increasingly busy and cosmopolitan neighbourhood. Streetcar tracks ran down a Euclid Avenue now dotted with a growing number of apartments and corner stores, but the Barber house and its inhabitants remain as a living link to Point Douglas’ disappeared settlement past: Edmund’s wife, Barbara, daughter of Robert and Mary Logan, lives there until her death in 1920, while her daughter Lily Sparrow stays in the house until 1959.

Barber House, the oldest house in Point Douglas, was built in the mid-1860s

1911 – The growth of Winnipeg reaches a crescendo, as the population reaches 136,000 — up from 42,000 a decade earlier. Much of the British immigrant working class — to say nothing of the city’s managerial class — that had settled in Point Douglas in the late 19th century is now gone, as the area transitions into a neighbourhood of Eastern European immigrants, primarily Russian Jews, but also a growing number of people from places like Ukraine, Poland, Romania, and Syria.

While much of the neighbourhood is made up of working classes, as well as a number of households living in desperate poverty, there is also a thriving Jewish merchant class, mainly clustered around Lorne Avenue on the north side of the CPR, and around Lily Street on the south side. A number of these households include live-in domestic servants.

Winnipeg’s place as Canada’s third-largest city and the centre of Western Canadian trade and finance in 1911 seems only more remarkable when compared to the rough settlement that existed only several decades before. It’s reasonable to assume at this time, that the city can only grow and improve. In Point Douglas’ future in particular, the industries along the CPR would only expand, the residential streets near the river would only increase in desirability, and the lives of the impoverished would only improve from new building codes and health and by-laws being proposed by Winnipeg’s Town Planning Commission.

What actually would occur in Point Douglas in the following century was beyond what anyone could have expected. Now an entirely complex urban neighbourhood, Point Douglas would continue to evolve, while facing the same kinds of challenges the Selkirk settlers did more than a century before.

Mother and child on Granville Street, circa 1911

—

Robert Galston likes to write about Winnipeg, urbanism, and other very, very exciting topics. Follow him on Twitter @riseandsprawl